Fumihiko Maki (1928 - 2024), chosen as the 1993 Laureate of the Pritzker Architecture Prize, is the second architect from Japan to be so honored—the first being Kenzo Tange in 1987.

Maki, who was born in Tokyo, studied with Tange at the University of Tokyo where he received his Bachelor of Architecture degree in 1952. Maki then spent the next year at Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan where Eliel Saarinen’s influence on the curriculum and as designer of the school’s buildings was significant.

He then took his Master of Architecture degree at the Graduate School of Design (GSD), Harvard University. His first apprenticeships were with Skidmore, Owings and Merrill, New York and Sert Jackson and Associates in Cambridge.

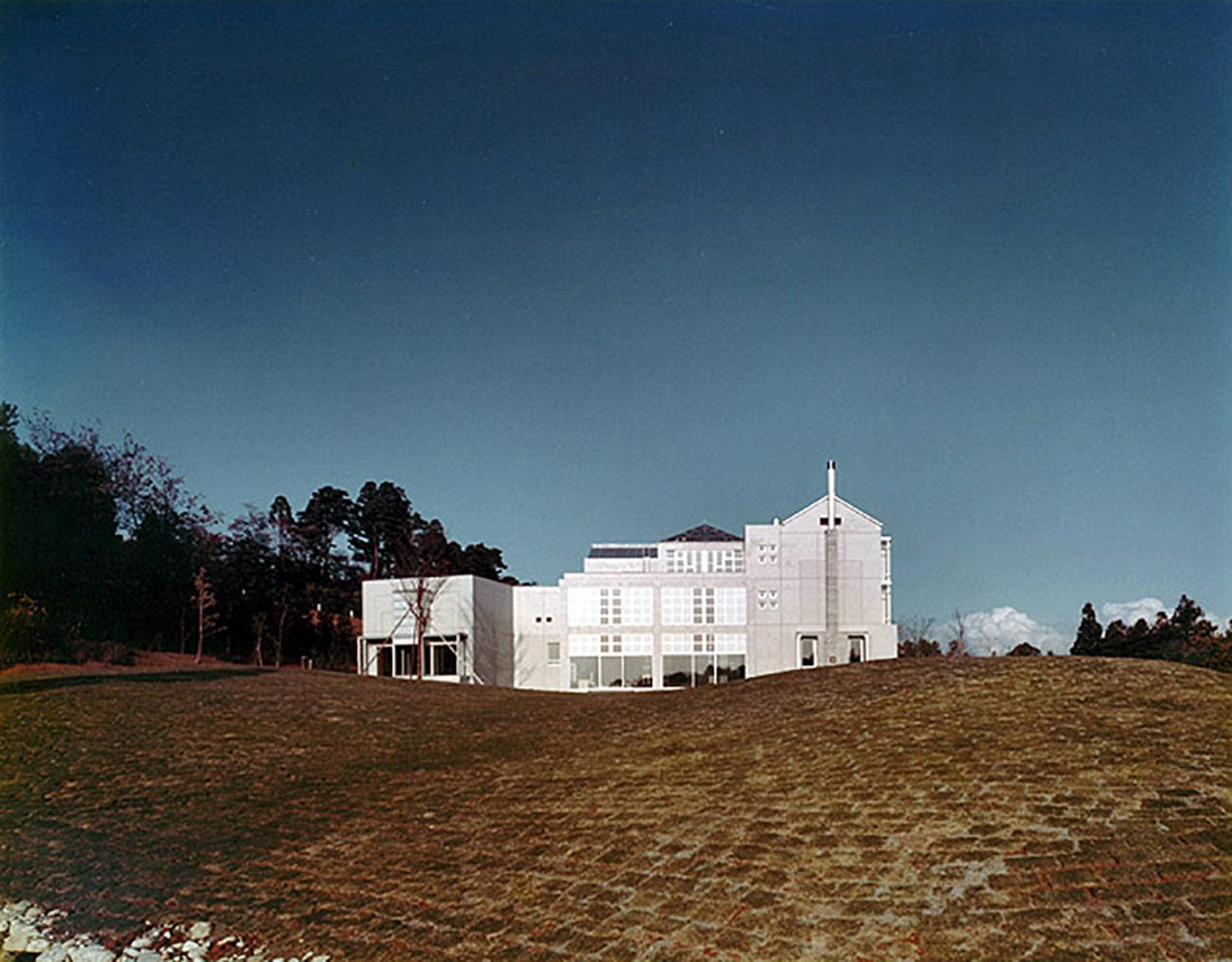

In 1956, he took a post as assistant professor of architecture at Washington University in St. Louis, where he also received his first design commission—for the Steinberg Hall (an art center) on that campus, which remains his only completed work in the United States. Following his four years there, he joined the faculty at Harvard’s GSD from 1962 to 1965, and has been a frequent guest lecturer at numerous other schools.

In 1965, he returned to Japan to establish his own firm, Maki and Associates in Tokyo. In the 28 years since, his staff has grown to approximately 35 people, with an equal number having passed through to begin their own practices. “I was never attracted to the idea of a large organization. On the other hand, a small organization may tend to develop a very narrow viewpoint. My ideal is a group structure that allows people with diverse imaginations, that often contradict and are in conflict with one another, to work in a condition of flux, but that also permits the making of decisions that are as calculated and objectively weighed as necessary for the creation of something as concrete as architecture.”

While he was preparing to open his own office, Maki worked at, or observed, numerous offices in Japan and other countries. One of the conclusions he drew was that an office, and by extension, design itself, is a matter of individual character, and that an office is itself a work of art. “Architectural design is perhaps the strangest activity undertaken by the many professions, and a group that engages in architectural design is likewise a curious organization. Architecture is a highly ambiguous field,” Maki continued.

Most of Maki’s work has been accomplished in Japan, although he is currently working on a number of commissions both in Europe and the United States. When his office building complex for Isar Büro Park near Munich is completed in 1994, it will be his first realized European project.

Later this year, a second realized work in the United States will be completed—the Yerba Buena Gardens Visual Arts Center, part of a large scale redevelopment in downtown San Francisco involving a number of prominent architects (Mario Botta, James Polshek, Mitchell/Giurgola, I.M. Pei). The Visual Arts Center by Maki is currently under construction, literally on top of the Moscone Convention Center.

Maki is the first to acknowledge that as a student, he came under the influence of post-Bauhaus internationalism. That plus ten years of study and work in the United States afforded him the ability to step back and take a view from a distance of both Japan and America, as well as other parts of the world. It is to this experience that he attributes what people have called an aesthetic sense that is intelligible to a world audience.

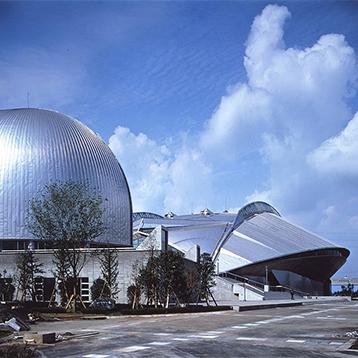

Maki calls himself a modernist, unequivocally. His structures tend to be made of metal, concrete and glass, the classic materials of the modernist age, but the canonical palette has also been extended to include such materials as mosaic tile, anodized aluminum and stainless steel. Along with a great many other Japanese architects, he has maintained a consistent interest in new technology as part of his design language, quite often taking advantage of modular systems in construction. He makes Fumihiko Maki, 1993 Laureate (continued) 2 a conscious effort to capture the spirit of a place and an era, producing with each building or complex of buildings, a work that makes full use of all that is presently at his command. As far as post-modernism is concerned, Maki has been quoted as saying, “In the West it might be all right, but in Japan, postmodernism using historic motifs would simply evaporate.” And with it, so evaporates the modern/postmodern debate as an issue of style. “The problem of modernity is not creating forms,” says Maki, “but rather, creating an overall image of life, not necessarily dominated by the concept of modernity.” For him, this overall image is in essence a question of space for human activity rather than a vision of a constructed facade. Maki often speaks of the idea of creating “unforgettable scenes”—in effect, stage settings to accommodate and complement all kinds of human interaction—as the inspiration and starting point for his designs.

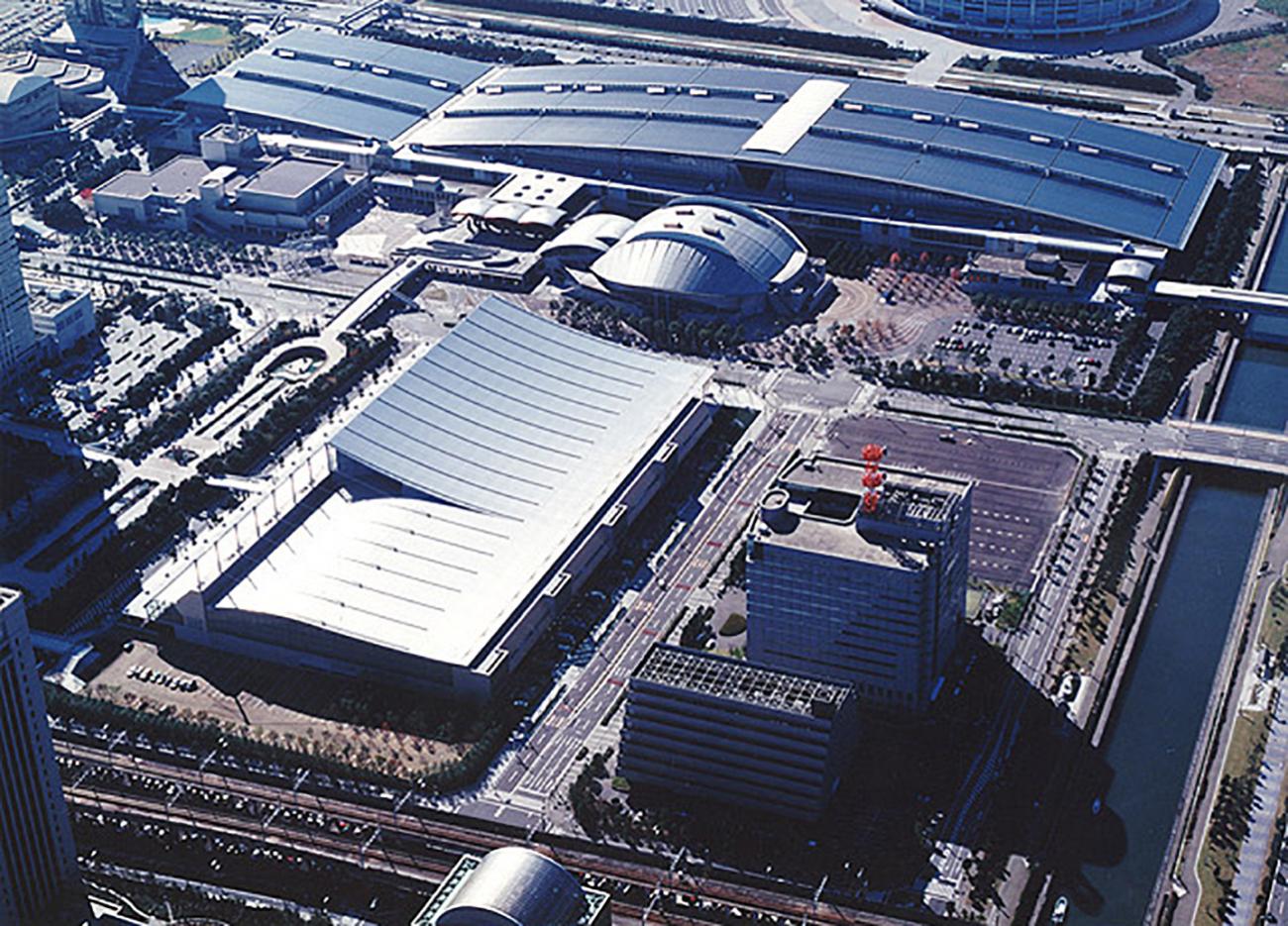

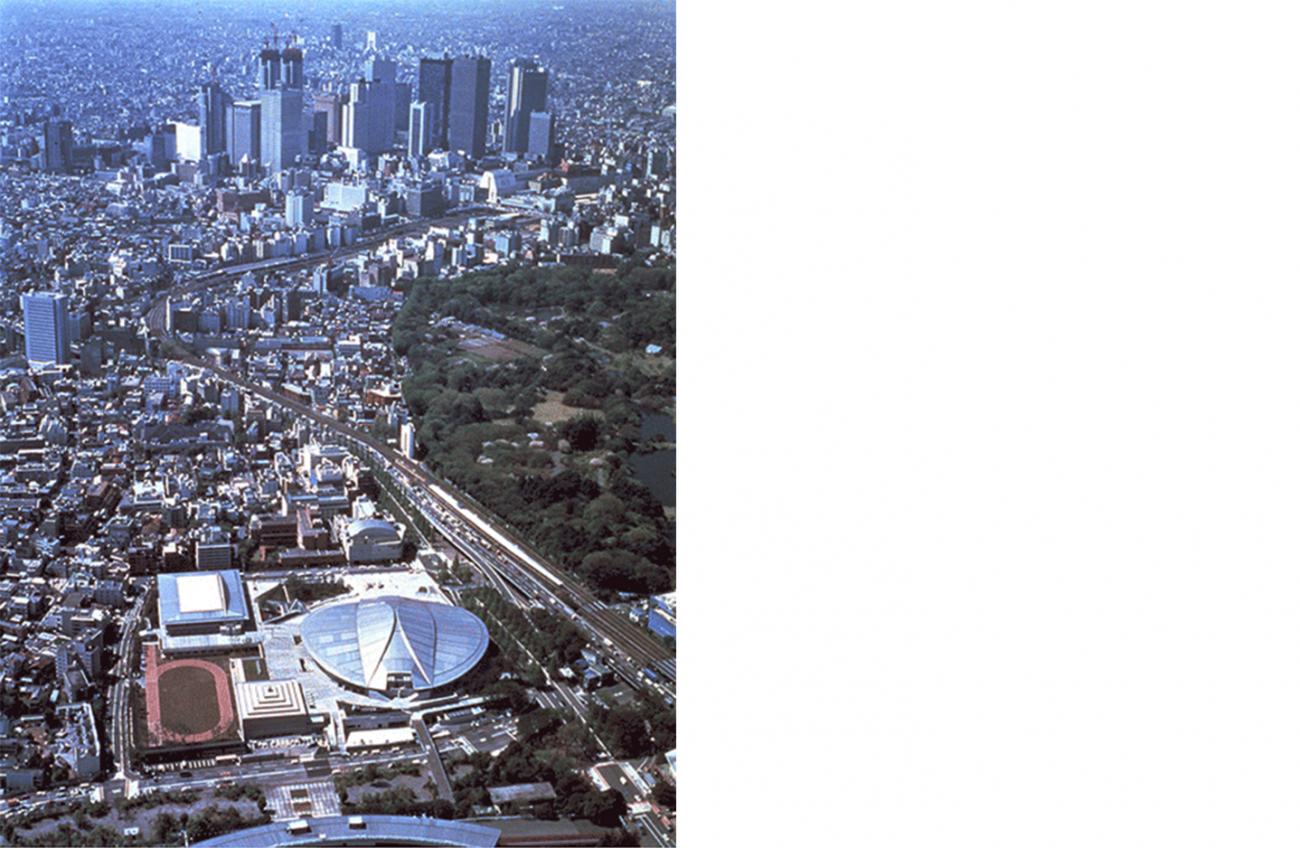

As a founding member of the Metabolists in 1960, his name became associated with the group’s large-scale urban designs and plans. However, his buildings are not “megastructures,” a term he invented. As Bill Lacy, in his book, 100 Contemporary Architects states, “His gigantic Nippon Convention Center in Tokyo shows how a huge building can possess qualities missing in the vast megastructures of the modernist years. The center...is modeled on the prototypical Japanese community nestled among hills and was intended to set the tone and direction for future urban growth in the area. Its vast volume and distinctive silhouette becomes a man-made mountain range in an otherwise flat, waterfront topography. The facility is organized along a central spine nearly one-third of a mile long and its vast exhibition hall is covered with a curved roof ... elements as background forms for a diversity of human-scaled components.”

Most critics agree that even with his most enormous buildings, Maki’s works are at ground level, scaled appropriately to provide human warmth and excitement. In Contemporary Architects, Ching-Yu Chang wrote, “While Maki has rightly gained considerable notoriety as a theoretician, he has clearly not allowed his thinking to become clouded with esoteric ideas. He applies his belief in module, standardized parts and adaptability for change in a very utilitarian, pragmatic way. It is apparent that the thrust of his design attention is not the glorification of these concepts, but the successful employment of them to create inclusive highly contextual architecture that is in strict accord with human, psychological preferences.”

Maki wrote as early as 1960, and it is still relevant today, “There is no more critically concerned observer of our rapidly changing society than the urban designer. Charged with giving form—with perceiving and contributing order—to agglomerates of buildings, highways, and green spaces in which men have increasingly come to work and live, the urban designer stands between technology and human need and seeks to make the first a servant, for the second must be paramount in a civilized world.”

In Maki’s Osaka Prefectural Sports Center, he unifies many separate spaces with a central spine, much like a street with different levels—in this case allowing access to the gymnasium at one end and to a restaurant, observation deck at the other. Here the diner can look back over a roof garden to an entrance plaza, in effect, looking through a layering of transparent planes and spaces—a concept that relates to many of Maki’s buildings.